Risto Conte Keivabu, an Italian with Estonian ancestry, writes that the global Estonian cultural festival, ESTO, is a great example of how culture, language, and tradition can be kept alive in a globalised world without falling into the trap of exclusive nationalistic sentiments.

Redefining a purpose

Preserving the tradition of the ESTO festival and keeping the Estonian societies abroad alive is not an easy task. ESTO festival was born by the will of the political refugees and expat Estonians who moved abroad before and during the Second World War. Their purpose was to preserve the Estonian culture and language abroad, while back at home, their country was occupied by the Soviet Union.

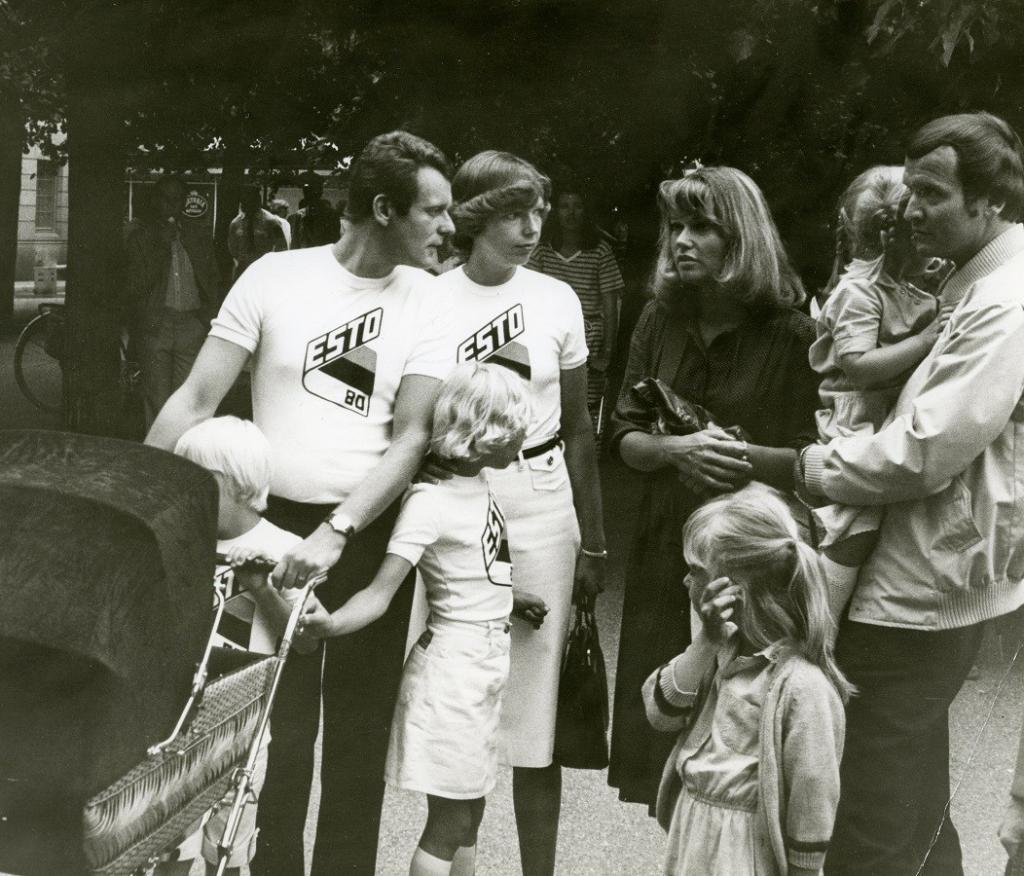

So, in 1972, the ESTO festival was launched. It gathered Estonians living abroad to celebrate the culture and traditions that united them and took place in Toronto. This year the XII edition of the festival was held from 27June to 3 July in Helsinki, Tallinn, and Tartu.

However, the original motivations of the festival do not exist anymore as Estonia has been a free country for almost 30 years. Therefore, the challenge for the ESTO festival is to reconsider its purpose alongside an independent and free Estonia. It also needs to work out how to engage a more varied community of Estonians living abroad – represented not only by the descendants of former political refugees, but also economic migrants of recent times.

Preserving identity

Similarly, the Estonian communities abroad face the challenge of passing their culture and language to the next generation in a globalised world in which traditions and local languages can be harder to preserve. Considering these challenges, the question of what makes someone Estonian becomes complex.

Is knowing the Estonian language fundamental? Is citizenship required? Is the individual identification with the Estonian culture enough? Does living abroad make someone less Estonian? If so, how to balance the need of giving global perspectives and knowledge to the native youth with the need of keeping the talents at home?

For the first time in 2019, the festival was also attended by youth delegates aged 16 to 26, from 26 different nations, representing their expat communities. The countries with the highest number of representatives were Canada, the US, Finland, and Sweden, mirroring the presence of dynamic and active Estonian communities in these regions. Despite having lived abroad for most of their lives, the delegates showed an impressive knowledge of the Estonian language, food, culture, history, and songs.

The programme for the youth delegates was very dense ranging from cultural activities and conferences, to workshops that allowed the youngsters to get acquainted with the Estonian culture, traditions and success stories of Estonian societies abroad. The aim was to inspire ideas for the future.

Global Estonians

Starting in Helsinki, the youth delegates had the opportunity to learn more about the strong ties that bind Finland and Estonia together. As Finland hosts the highest number of Estonians living abroad, around 50,000 expats, the transmission of Estonian culture and language are critical.

Estonian schools and organisations try their best to achieve this goal and it was interesting to have a traditional Estonian dinner, accompanied by the traditional dances in the Alppila church that is used by the community in Helsinki. The programme continued in Tartu, where during the Youth Congress, delegates had the opportunity to discuss critical questions regarding their Estonian identity.

The discussions then continued in Tallinn. During an event entitled “Global Estonians”, organised by the Estonian World Council, the speeches and panels held by the Estonian president, Kersti Kaljulaid, Estonian politicians, and representatives of the Estonians communities abroad, touched on many critical aspects regarding Estonian national identity and its preservation abroad.

The will to create strong bonds between national institutions and the expat organisations was raised several times. Similarly, the need to create online Estonian language courses or to support the already existing Estonian language classes abroad were also discussed. However, developing concrete ideas to attract expat Estonians back to their homeland, or how to better integrate the minorities living in Estonia, is more complicated.

Language and tradition can be kept alive without aggressive nationalism

In a globalised world, in which individuals relocate from one country to another, it becomes difficult to define what determines how a person belongs to a national identity. On one hand, natives who have spent a long time abroad might have lost their identification with the homeland and find it difficult to reintegrate when returning. On the other, there are people who have migrated to another country and feel more at ease in the host country than in their homeland.

The ESTO festival and the Estonian societies abroad are a good example of how the preservation of a population’s culture and language can be achieved without falling back on nationalistic sentiments. “Estonianness” is something that united all the youth delegates coming from the 26 different countries.

For some, this meant speaking Estonian and attending the Song Celebration, visiting relatives living in Estonia, and participating in the activities of the Estonian societies in their local towns. For others, being Estonian meant to remember the history of relatives that escaped the Second World War, to know traditional songs and dances and to love the food – especially the dark rye bread and “kohukesed” (a curd snack, originating from Latvia, but now also very popular in Estonia – editor). Some considered themselves expat Estonians, or as Estonians temporarily living abroad, and others as foreigners with Estonian roots.

The variation of what “Estonianness” means to each of the youth-delegates is an example of how differently individuals form, relate, and define their national identity. For this reason, the tradition of the ESTO festival and the activities of the Estonian societies abroad are worth keeping alive. Their concepts could be expanded to other national contexts, offering a great example of how culture, language and tradition can be kept alive in a globalised world without paying the cost of falling into the trap of exclusive nationalistic sentiments.

Cover photo: ESTO 2019 celebrated at the Estonian National Museum in Tartu. Photo by Arp Karm.

Author Risto Conte Keivabu is a PhD student in social and political sciences at the European University Institute in Florence, Italy. He did his bachelor’s degree in international relations at the University of Padua, Italy, and his master’s in comparative public policies at the Southern Denmark University. Keivabu moved to Italy when he was five, but he always felt a strong connection with Estonia, thanks to his mother who spoke with him in Estonian, and his relatives who always welcomed him back in Estonia.

Article was published in Estonian World.